There has been a highvoltage chorus of disapprovals in India and in the Western media over raids against high-profile politicians, like the members of Congress’ ‘first family’ such as ‘empress’ Sonia Gandhi and her ‘unbecoming princeling’ Rahul, and their interrogations by the country’s investigation agencies over the issue of corruption and money-laundering. Earlier also, the dynasty’s son-in-law Robert Vadra was meted out similar treatment over the issue of corruption and land-grabbing.

All these started post GE2014 in which the Congress party was badly mauled as it could muster just 44 MPs in the Lower House, the worst performance the grand old party had ever registered. Almost the same result was repeated in GE2019 in the country’s firstpast-the-post voting in practice since Independence and as per the constitutional mandate with further decrease of overall fall in vote percentage. Though the Congress won marginally higher number of seats this time, it was much less in number to cobble up a 2004 or 2009 type of coalition with “like-minded” parties to capture power.

On the issue of raids, even people of eminence went on to shout from the rooftops: “ED saves Gandhis in Congress power game”, “Not every hero is a martyr, but every martyr is a hero”, “The party’s first family must be hoping for their martyrdom at the hands of the Enforcement Directorate as the key members of the family targeted giving them hero status”, so on and so forth. They give the example of Indira Gandhi’s arrest, who was targeted by the first nonCongress party government in late 1970s for her undemocratic adventures during imposition of draconian Emergency in the country, which rather unleashed the family’s inner martyrdom. As her grandchildren now jump the barricades and wag fingers at those in power, and are also getting disproportionately high visibility on the prime time TV for no valid reasons, will these acts convert into votes like their grandmother managed to do in 1980? This is, indeed, a billion dollar question.

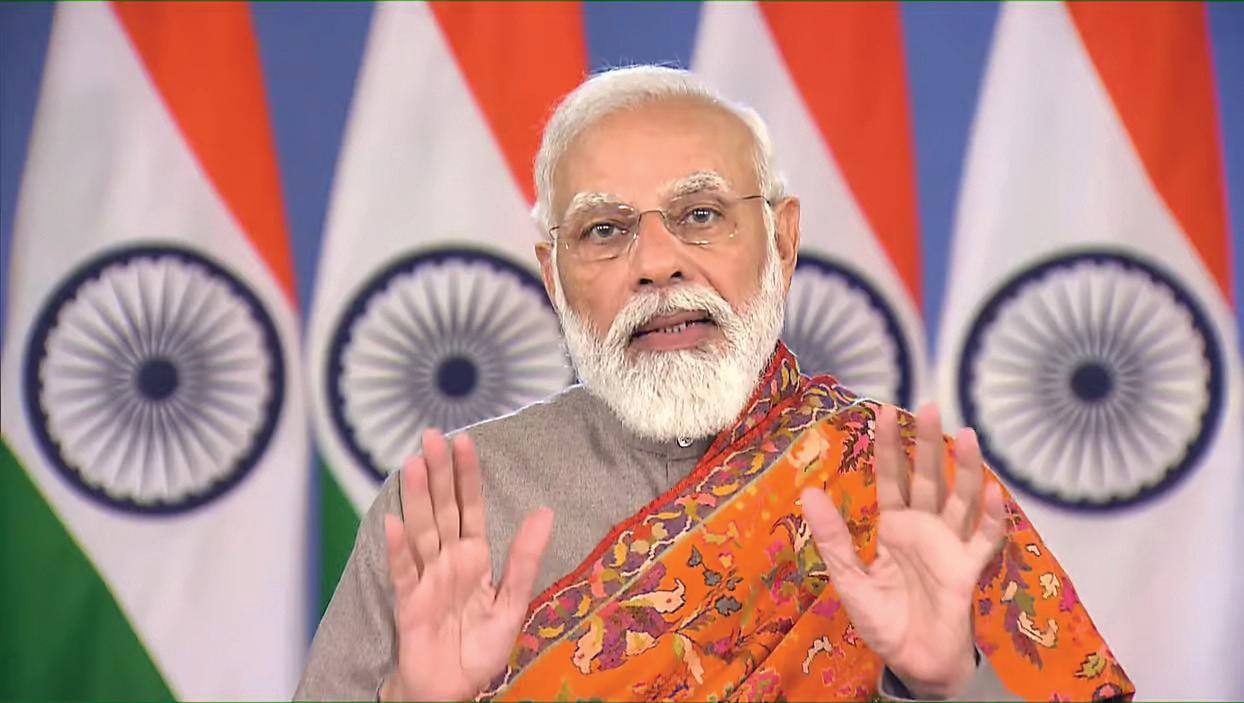

No doubt Sonia Gandhi’s high publicity visit to ED office – unlike Modi’s visit to SIT office alone and without publicity for several days, has enhanced the recall value of the Congress as the principal opposition party. The result: Brand Gandhi, which is on the verge of eminent decline, has turned the beneficiary of the media blitzkrieg. While many among the eminent writers and commentators are happy while some others are unhappy over the ED action with full backing of the judiciary. Recently, the Supreme Court in its verdict upheld the provisions in PMLA 2002, the Act that empowers the ED to conduct the raids and the interrogations. Meanwhile, those raided are now conveniently playing the victim card and crying hoarse claiming that they are at the receiving end of the ruling party’s vendetta politics. Now, let us discuss the Indira Gandhi’s so-called political martyrdom in late 1970s. Many argue that unsustainable actions against Indira during electorally mandated but incomplete tenure of the first non-Congress experiment in independent India was the single major reason of her return to power within three years of her and Congress’ electoral eviction from power. But, this author refuses to accede to this argument for the reasons such as: Firstly, the then ruling Janata Party, though was seen on the surface a single entity and formed the government accordingly; internally, there was no ideological convergence as that was an amalgamation of many political parties from diverse backgrounds such as Socialists, Centre-Left, Centre-Right, etc., who had joined hands hurriedly to kick out the dictatorial Indira-Sanjay regime from power and save the country’s democracy. But later it only resulted in conflicts over policy formulations and lack of united face of governance.

Apart from the above, some prominent ministers in the government found losing their ideological bases they had assiduously cultivated over decades of struggles at the grassroots level. This was the primary reason behind the fall of the Janata government. Secondly, the selection of the leader to head the government as the Prime Minister was not based on his popularity or votes he had garnered for the new party or the number of MPs loyal to him, but based on experience of as a politician with ministerial experience in the previous governments. This was the kind of mistake that had taken place in 1947 when Sardar Ballavbhai Patel’s electoral win was overlooked. However, all politicians are not of Sardar Patel’s essence. Patel’s only concern was nation building, and thus he acceded to Gandhiji’s undemocratic imposition of Nehru as the PM, instead of becoming part of a power struggle with a power-hungry Nehru during the early days of Independence.

It may be safely assumed that Patel the Great might have accepted Gandhiji’s decision with an objective to show the world and then British PM Winston Churchill, who had already branded the Indian leaderships as “a bunch of rascals” and opined that “they cannot rule themselves unitedly”, that the newly-independent country’s leaders were different. Despite betrayal of the democratic verdict under the watch of the “father of the nation”, early independent India’s government survived from possible a powerfight as seen in several newly independent countries around the world those days, and also in late 1970s during the Janata regime, on the foundation laid by Sardar Patel. The early failure of the ‘Janata experiment’ was the prime reason of Indira’s return to power in 1980 as she had successfully man- aged to convey the message that the nation needed a strong leader which only her dynasty could offer, and that the non-Congress leaders were just a bunch of power-hankering politicians. Her earlier careful cultivation of her and her family-centric hero-worshipping worked handy in her return to power. But her and her dynasty-centric dominance did not work in 1989, and it was the Indira, Rajiv governments’ subsequent decade-long widespread corruption that caused Rajiv Gandhi’s and the dynasty’s fall from power.

Here, I would like to mention that, had Indira not been assassinated by her own security guards in 1984 and following which her son not created an euphoria of ‘vote for the orphan’, the subsequent general elections would have thrown up a different verdict not matching with GE1980 as people by then had started distasting their own foolishness in supporting the Gandhis’ corruption-ridden dynastic politics in the country for decades. Now, the mute question is: Should the government abandon the ‘crusade against political corruption’ for ‘political correctness’ which may lead to ‘validation of corruption’ and make it ‘an integral part of nation’s politics’? My answer is: It MUST NOT. Therefore, one more question arises: Who should lead this movement? Certainly the man who has proved that the corruption stink can’t even touch his skin and is not a product of nasty dynastic politics, nor does he nurture dynastic ambitions. The above analysis clearly shows that people want a government in New Delhi which has a ‘clean image’, has ‘strong leadership abilities’ and displays ‘governance skills’. Subsequently, the same can be simulated in the state capitals as well. The apprehension that Indira Gandhi’s so-called martyrdom in late 1970s getting copied by her grandchildren to get back to power may not be feasible in 2020s as the political environment in India has gone through a lot of political changes.

The water of Narmada is no more getting wasted in Arabian Sea, rather it irrigates the farm lands in the distant Kutch desert, despite several decades of opposition by the West-funded socalled environmentalists, who on the one hand lead agitations against water shortage and on the other hand over farming and submerge of forest land in the catchment area. Hence, as the nation celebrates Azadi Ka Amrit Mahostav to commemorate the country’s 75th Independence Day, no doubt the present dispensation’s decisive drive against corruption, which taxed India’s economic development for decades and poisoned its political sanctity at every level, should be encouraged by all and sundry, irrespective of their political and ideological affiliations.

(The author is a Senior Research Fellow in Defence Research and Studies ‘DRaS’, Ernakulam, and a faculty of Management Studies in Trident Group of Institutions, Bhubaneswar)

Opinion3 years ago

Opinion3 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Fashion8 years ago

Fashion8 years ago

Opinion4 years ago

Opinion4 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Politics8 years ago

Politics8 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago