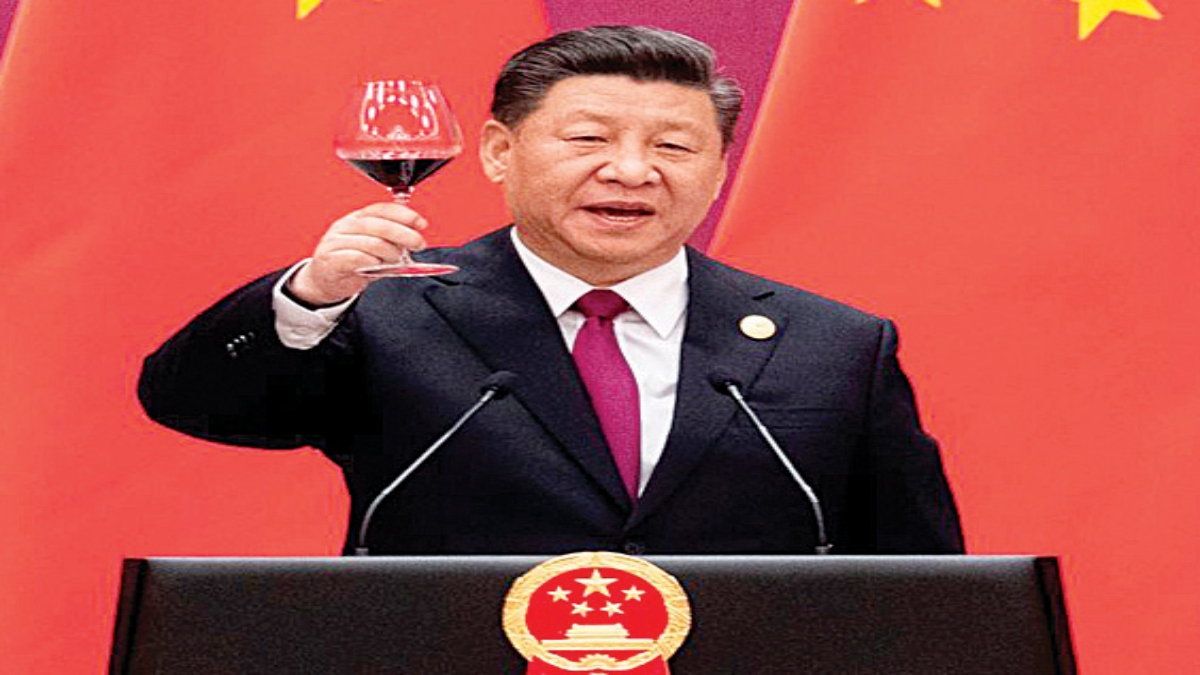

Chinese President Xi Jinping has stepped out of the country for the first time since the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic that originated in his country in early 2020 and forced global lockdowns, clobbered large economies and caused death of thousands across the world, not to forget the millions who fell sick and escaped death but paid with lifetime of infirmities.

But, we won’t discuss the pandemic here even though any discussion in the world today is incomplete without mentioning the affliction that has acquired a universal character.

Xi, wearing a face mask, landed in Nur-Sultan, the capital of Kazakhstan, to a red carpet welcome by his Kazakh counterpart Kassym-Jomart Tokayev on Tuesday. The Central Asian republic is celebrating 30 years of the establishment of diplomatic relations with China.

Central Asian countries are of strategic interest to China not only because they can help the second largest economy deepen its economic footprint in the region but because they also provide a diplomatic perch to ride on as Beijing faces increasing isolation from the West.

Later in the evening, Xi flew to Samarkand in Uzbekistan where he will attend the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) Summit from Thursday to Friday. Beyond the security implications of the meeting of the strategic group of eight countries, the spotlight on Samarkand this fall is on bilateral talks.

Though Xi is thousands of kilometres from home, his heart would be in Beijing as the Chinese leader who would be virtually crowned for the third term to lead the nation of 1.5 billion is just two months away from the grand event – the upcoming Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC).

Xi carries loads of baggage on his shoulders. The baggage is made of political pledges and expectations, declarations of social and cultural resuscitation of the nation and the promise of reuniting Taiwan with mainland China.

Xi is in Samarkand not only as the President of his country but as a reservoir of hope for the millions of Chinese of his generation who want to live by the ideals of communist leader Mao Zedong and believe in the revival of an ethos that the China of today may have strayed away from amid lapping waves of globalisation and the unnerving war cry of capitalism over communism.

The presence of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Russian President Vladimir Putin at the summit adds to the precariousness of Xi’s situation. While northern neighbour Russia is seen as a renegade by the West for attacking Ukraine and bringing the region to a military ferment, India has to speak its mind to Beijing that was behind the Galwan standoff which brought two nuclear powers quite close to a full-blown war.

A Xi-Putin summit will see the Chinese President trying to leverage the opportunity to buy more support from Moscow for its stance on Taiwan. President-for-life he may be, but nothing prevents Xi from catalysing more support from a country that again stands isolated among most nations of a community comprising mainstream international politics.

Ahead of the 20th CPC National Congress on October 16, Xi has to show his constituents (Chinese people) that he is capable of standing tall in the Great Hall of the People.

In Modi, Xi will find an adversary who straddles the eastern and western hemispheres with equal ease. In the summit with Modi, Xi will try his best to turn the tables on India over the spy ship Beijing sent to Sri Lanka or have the upper hand on border disputes with New Delhi. After all, the delegates at the 20th Congress need to see their leader unfazed.

But Modi is no political novice. He surely has his cards close to his chest and would not be cowered by the flaming dragon. If communism has steeled Xi, democracy has strengthened Modi.

“We should join hands to combat terrorism, separatism, extremism, drug trafficking and transnational organised crimes, and ensure the security of oil and gas pipelines and other large cooperation projects and their personnel. We should resolutely oppose interference by external forces and work together for lasting peace and long-term stability of our region,” Xi said in a signed article published on Tuesday in the Kazakhstanskaya Pravda.

If words were horses, all politicians would ride them. Let’s see which way the dragon sits and the elephant trumpets.

• IANS

China emerged as the world’s second-largest economy by registering exceptional growth in the last four decades but at the cost of widespread corruption, environmental degradation, food safety issues and income disparities.

Prof Justin Yifu Lin, formerly senior vice-president and chief economist of the World Bank (2008-12), in an analysis explained the institutional price China paid for its economic success, reported Financial Post.

In 2018, China celebrated the 40th anniversary of its transition from a planned economy to a market economy. And it was an astounding success. In 1978, the country was closed and suspended to the world. It was a poor country, if not among the world’s poorest.

Its per capita was less than a third of even sub-Saharan African nations. Over 80 per cent of its people lived in rural areas, as many were living below the international poverty line and China had a closed economy where trade made less than 10 per cent of its GDP.

But in the last 40 years, the annual GDP growth rate was 9.4 per cent on average and trade grew at an average rate of 14.8 per cent. In no time, China was the world’s second-largest economy overtaking Japan. It was the largest exporter, beating Germany. It even surpassed the US to become the largest economy, measured by ‘purchasing power parity,’ and the largest trading economy.

But China paid a price for its unprecedented success. In addition to environmental degradation and food safety issues, which have attracted many public complaints and are the results of rapid industrialization and lack of appropriate regulations, the main issue during the transition is widespread corruption and the worsening of income disparities, said Prof Lin.

“Before 1978, China had a rather disciplined and clean bureaucratic system and an equalitarian society. According to the Corruption Perception Index published by Transparency International, China ranked No. 79 among all the 176 countries or territories in 2016,” added the professor.

The negatives are attributed by economics experts to China’s “dual-track transition strategy”. At one level, “the government provided transitory protection and subsidies to the nonviable state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in the old, capital-intensive sectors to maintain stability”.

At another, it “liberalized and facilitated the entry to the new, labour-intensive sectors which were consistent with China’s comparative advantages to achieve dynamic growth,” reported Financial Post. Prof Lin points out that one of the most essential “costs of investment and operation for the old capital-intensive sectors was the cost of capital”.

Before the transition in 1978, the “government used fiscal appropriation to pay for investments and cover working capital, so SOEs did not have to bear any cost for capital. After the transition, the fiscal appropriation was replaced by bank loans.”

The Chinese government set up four large state banks and a stock market to meet the capital needs of large enterprises and to “subsidize SOEs, the interest rates and capital costs were artificially repressed”.

The research shows, “When the transition started, almost all firms in China were state-owned. With the dual-track transition, private-owned firms grew and some of them become large enough to get access to bank loans or list in the equity market.”

“As interest rates and capital costs were artificially repressed, whoever could borrow from the banks or list in the stock market was therefore subsidized. These subsidies were paid for by the low returns to savings in the banks or in the stock market made by individual households. Those people providing the funds were poorer than the owners of the large firms they financed.”

“The subsidization of the operation of the rich’s firms by poorer people was one reason for increasing income disparities. Moreover, the access to bank loans and equity market generated rents, leading to bribery and corruption of the officials who control the access.”

The analysis argues that some natural monopoly industries, such as power and telecommunication, were operated by state-owned enterprises and the government “liberalized the entry to those industries gradually”, adding that “those monopoly rents were also sources of inequality and corruption,” reported Financial Post.

Opinion3 years ago

Opinion3 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Fashion8 years ago

Fashion8 years ago

Opinion3 years ago

Opinion3 years ago

Politics8 years ago

Politics8 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years ago